Inventory 101 for breweries and roasteries

This post, just based on the title alone, will probably be in contention for the most boring blog posts I’ve ever written, and fuck me I’ve written some bad ones. Also a quick disclaimer, I’m no expert in this stuff and this is not financial advice. Feel free to add to the comments below if you think the content can be improved.

But I’m writing this post for a few reasons.

- I believe finance is by far the most important thing for physical business owners to understand and I don’t think it’s well understood. One of the biggest areas where finance goes bad, is due to misunderstanding inventory.

- Inventory is super hard and I only feel like I’m recently starting to get my head around it. I ran a physical business for many years without understanding this stuff.

- I recently bought a coffee roasting business (East Coast Roast), and I’m currently deep in figuring out inventory, so now is a good time to write it.

Related: Inside the P&L of my coffee / cafe supplies business East Coast Roast

Background

For the first 12 years of my career as a founder I only had online businesses. Starting a physical business back in 2015 (Black Hops Brewing), was a huge change. It grew quickly from an idea in my mate’s garage ,to a company doing $16m in annual revenue with 70+ staff.

I’m no longer involved in any way at Black Hops, but towards the end, I learned a lot about finance and inventory. And after purchasing my coffee business last year, I’m still deep in understanding it and putting in processes to make sure things stay on track.

I’ve found that this stuff isn’t very well taught at business school or among founders, because it’s pretty boring. I’ve also found that advice from accountants on this often isn’t the answer. To manage inventory well, you have to understand it yourself, because in a physical business it’s something that requires managing every single day. I’ve seen this handled extremely poorly in the past, and it can be catastrophic to the business. Inventory is core to understanding the financial position of your business, and if you don’t understand that, you are in a bad place.

Inventory Components

In order to have a complete inventory process, you need all of the following:

- Fundamentals – Balance Sheet and P&L set up correctly, and some decent software that can account for all of this properly.

- Purchasing – A process for purchasing that correctly places goods in the right place on the Balance Sheet.

- Production – A process for documenting the conversion of raw materials and packaging into the final product, including Work in Progress (WIP).

- Sales – A sales process where when goods are sold, the true costs of those specific goods sold are accurately accounted for.

- Stocktakes – A process for checking that all of the above is working and accounting for the $ where it’s not working.

Component No. 1 – Fundamentals

As a starting point, you need to have the following fundamentals sorted.

P&L vs Balance Sheet

Before digging into inventory it’s critical that you understand the difference between the P&L and the Balance Sheet. If you do, you can probably skip this section, but I think so few people really understand the difference, this section might just be helpful.

As a founder I’m guilty of only really keeping an eye on the P&L, and if it looks good, I feel good about the business. In fact for my first 12 years in business, I didn’t even really know what a Balance Sheet was, it’s not really a thing in online businesses.

But in a physical business, understanding the difference is extremely important. I’ll use coffee as an example because it’s a reasonably simple business.

In a business, a monthly P&L will tell you where you are at in any given month in terms of your income vs your expenses. For a small online business, the equation is very simple. How much did you spend this month and how much did you make?

For a physical business however, things are different. The idea of the P&L is to give you a snapshot of where the business is currently at. But to do that, the P&L needs to tell you not what you spent that month, but what you spent in your efforts to earn the income that you earned that month.

Here’s a simple example.

Let’s say in January we bought 200kg of green coffee beans at $10 / kg. That’s $2,000. And we roasted half of it (100kg) and we sold that at $20k / kg, which is also $2,000. This is a pretty decent business, you are buying something, undergoing a small process and doubling the value of it (50% gross profit). In a business with no balance sheet, you would have $2,000 worth of green beans as an expense and $2,000 of roasted beans as income and the business would break even (0% gross profit). But you’ve only used half of the beans. The following month you sell the other half and you’ve got no costs (100% gross profit). You can see how accounting for things like this can be problematic.

So in a more accurate way of accounting for what has happened, you use the Balance Sheet. The Balance Sheet is basically a whole group of made up accounts where you can store things.

Doing things properly, in the example above when you made the purchase of $2,000, you would allocate that to the Balance Sheet, not the P&L. So far the business has no expenses for the month. As you earn the income, you’d move that green bean off the Balance Sheet to the P&L, so at the end of the month you would have $1,000 sitting on the Balance Sheet as if it was cash in the bank, and $1,000 in costs on the P&L, accurately reflecting the fact that the business made a $1,000 profit (50% gross profit).

That’s an oversimplified example, but that’s how you need to manage finances in a physical business. And it’s actually quite difficult to do without good systems.

There are essentially 2 ways to do it:

Option 1- Have an accounting or ERP system that manages all of that for you.

Option 2 – Manage what you can in the accounting system, and manage the rest in another system. Then you go back to the accounting system and update it with your estimates.

Obviously if you can make option 1 happen, that is the best way to do it and as a business grows, option 2 is no longer really an option.

COGS

A really important part of this is having your P&L set up correctly so that at the top of the P&L, all costs associated with making the product are correctly covered under Costs of Goods Sold (COGS). Some of this will be super obvious. For example when you make beer, the grain and hops are raw materials, those are accounted for in COGS. In coffee, it’s green beans. Then there’s packaging, that should also be in COGS. But there are also some less than obvious things like:

- A % of the rent (about the amount that is needed to produce the product). In beer for example the rent would be apportioned between the taproom and the brewery itself. The taproom rent is separate, the brewery rent is considered part of COGS.

- Direct labour – A brewer or a roaster in coffee are directly working on producing the product. You can’t have the product without the labour, if you lose the labour you can’t make the product. This is considered part of COGS.

- A % of services like gas and electricity – much like rent above, if you need it to make the product it should be part of COGS.

What you are left with, is an accurate reflection of how much it costs you to make a product, and how much you make from the product. This is the gross profit, and if your gross profit is healthy, your business should be able to scale up and down without too much trouble because as your production goes up, your costs go up by less and there is profit left over (assuming overheads remain about the same).

You can check out my recent monthly P&L to see this in action.

Related: Inside the P&L of my coffee / cafe supplies business East Coast Roast

Systems

All of that sounds good but it’s often not super easy to put into practice. One of the stumbling blocks I’ve found for small businesses is that Xero has pretty much taken over when it comes to small business accounting. This is something I celebrated when it happened because I hated MYOB so much. But Xero sucks at inventory and you can imagine, for such a critical financial issue, it’s a big risk to do this outside of the accounting system (option 2 above).

At East Coast Roast, I’ve gone back to using MYOB for that exact reason. MYOB sucks in so many ways, I won’t even get into it. However it is awesome in one super critical way – it handles inventory properly, and Xero doesn’t.

I’m running inventory as per option 1 above and throughout the rest of this article, I’ll use that as an example.

If you are using Xero, you are probably doing option 2 which is basically estimated inventory and then updating the accounting system – this is very risky unless you have a very good inventory person doing it for you.

Component No. 2 – Purchasing

To make physical products, you typically need to have a facility (rent, services), use direct labour (discussed above) and then you need to make them out of 2 things, materials and packaging.

For example a 1kg bag of coffee contains:

- Materials – A combination of around 1.2 kg of different blends of green coffee beans (there is weight loss during the roasting process).

- Packaging – A bag for the blend of that coffee, and sometimes a sticker.

Quite simple, which is a nice change for me coming from beer which is a bit more complex.

- Materials – Beer would have malted barley, hops, yeast, water, sometimes some other adjuncts for fancy beers like coffee or fruit.

- Packaging – If it was a can you’d have cans, lids, sometimes labels, 4 pack holders, carton boxes, pallets and pallet wrapping.

Out of interest, one of the trickier parts of this for beer is how to manage yeast which is typically ‘grown’ by breweries. That makes it very difficult to account for properly!

Regardless of what materials or packaging are needed, they must be accounted for on on the Balance Sheet in inventory. You spent the cash, but from a P&L perspective you haven’t actually incurred the expense until you use the materials. Obviously that basic calculation assumes you never lose any materials or packaging, but in the real world you do. This is where stocktakes come in, which we’ll run through further down.

But for now, understand this. If you run a business that makes a physical product, and you purchase raw materials or packaging, those purchases should not show up on your P&L. They should show up on the Balance Sheet, until they are used in the products you sell. This sounds simple, but accounting for materials used in products you sell requires very good systems, more on that later.

Component No 3. Production / WIP

All products are made by taking materials and packaging and using a facility and direct labour to turn them into something else.

When you combine materials and packaging to make the product, you need to account for that change. This typically happens in 2 ways:

- If the process is fairly complicated, you will make an inventory adjustment that takes the raw materials and turns it into Work in Progress (WIP). This is a different account on the Balance Sheet. An example is when you brew beer you combine all (or most) of the ingredients and then it sits in the tanks for 3 weeks. The raw materials should be converted into WIP throughout that time and only after that process is completed, it will be transferred into finished goods (something you can sell).

- Thankfully these days for me the process is much simpler. In the coffee business green beans are converted into roasted beans in about 20 minutes and we pack them on the same day, so there is no WIP really. We just put one adjustment in where we take the green bean and we convert it to roasted bean ready to sell. This is still all on the Balance Sheet because you still haven’t sold any of the beans, so you haven’t really incurred the cost against the income.

Component No 4. Sales

This is the critical step. When you make a sale, you need to account for the direct costs associated with that sale. MYOB does this in a really neat way using Builds.

- When I sell 1kg of East Coast Roast Coastal Blend (add it to an invoice), MYOB essentially ‘builds’ the sale using a predetermined recipe of what the product is made up of (raw green beans and packaging) and the costs for those items are added to the P&L as COGS as part of that transaction.

- So over the course of a month for example, the P&L will list all 1kg coffee bags sold and also only list the costs directly associated with the materials and packaging used for those sales. Nice and simple and gives you an exact picture of where the business is at in terms of revenue vs the costs associated with that revenue.

This is the part that other accounting systems like Xero don’t do very well, and it’s the reason why companies look at full blown ERP systems, or some kind of spreadsheet shortcuts to manage inventory.

Component No. 5 Stocktakes

All of this falls apart without a good system for stocktakes.

Stocktakes are not about counting stock and updating a system to reflect how many of each thing you have. Stocktakes are a check to have in place, that will show you how imperfect your inventory accounting system is, and that enables you to properly account for that imperfection, to effectively make it perfect again. It’s the final loop in the process, and without it the process is useless, and your numbers are hypothetical and not real.

For example, what happens if you order 1,000 labels and you lose 100 of them in the labelling process? What happens if you order 1,000 labels and then you rebrand and don’t use 500 of them. What happens if you lose a batch of coffee? What happens if someone steals a few kg of coffee? What happens if you deliver the wrong product and no one notices? What happens if you are sent the wrong products and no one notices? What happens if your assumption around how much raw materials and packaging are needed to make the final product, are actually wrong? Once you start properly doing stocktakes it will blow your mind how inaccurate your assumptions are!

These things happen all the time in physical products business, which is why you need a proper stocktake.

A stocktake should do the following:

- Give you a number of all of the items you expect to be in stock on the Balance Sheet.

- Allow you to count what you actually have in stock in real life.

- If you have less than expected, you can take that amount off the Balance Sheet and add it to the P&L as an expense and you can correct the system so it reflects what you actually have.

Essentially it makes sure your hypothetical numbers are right and if they aren’t, it picks the mistakes up as a cost on the P&L – so they are accounted for even if they are wrong. This is a huge thing because no one wants more costs on their P&L, and if you start doing it and start measuring the expenses, you will get much better at minimising it. But more importantly if you don’t do this process, all of your financials will be wrong and that is a HUGE risk.

Again, MYOB is quite good at this.

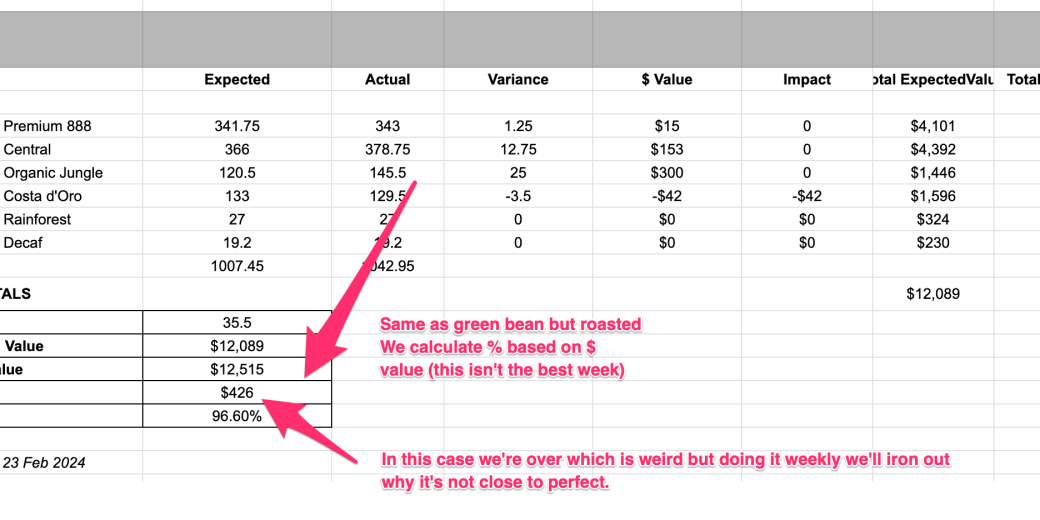

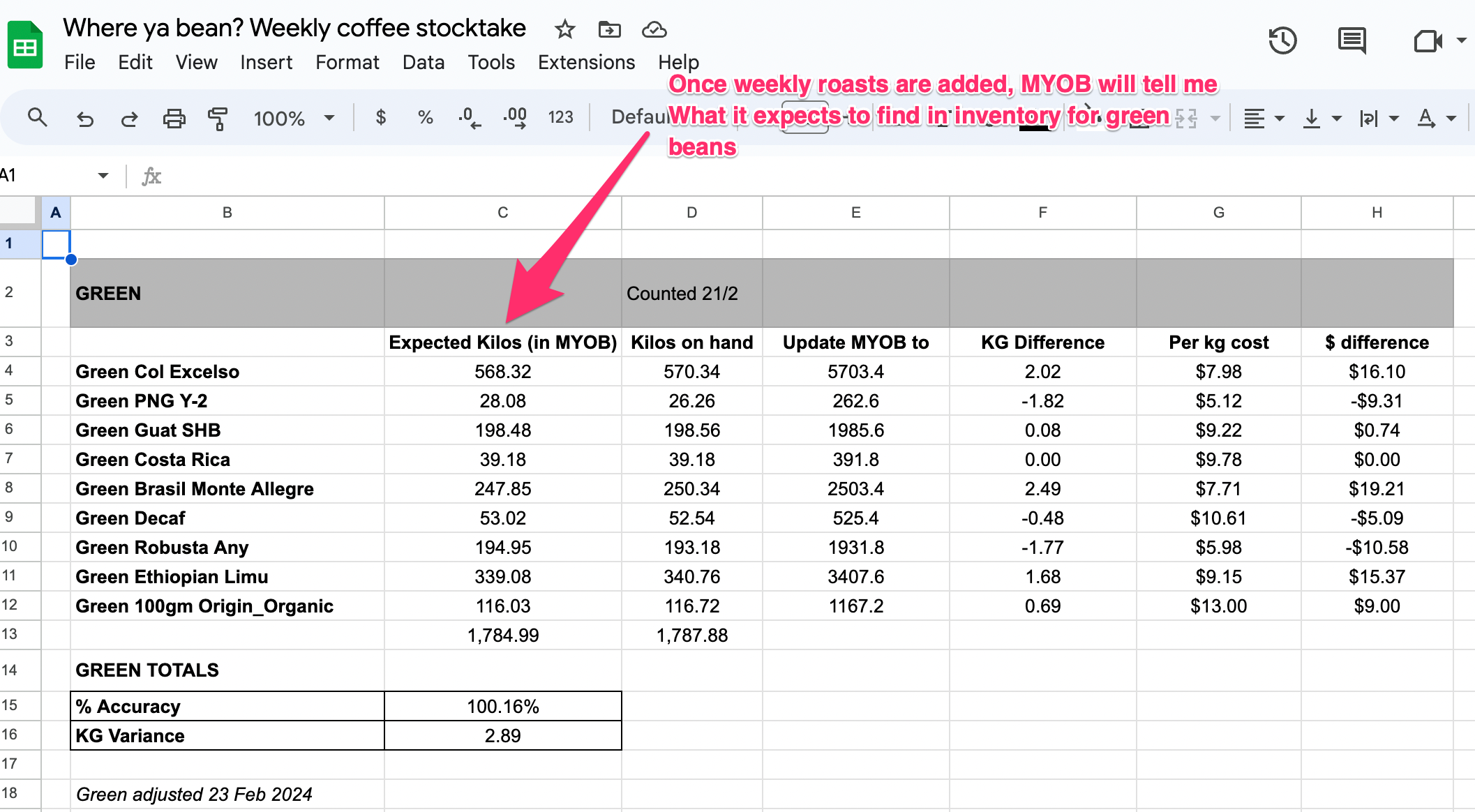

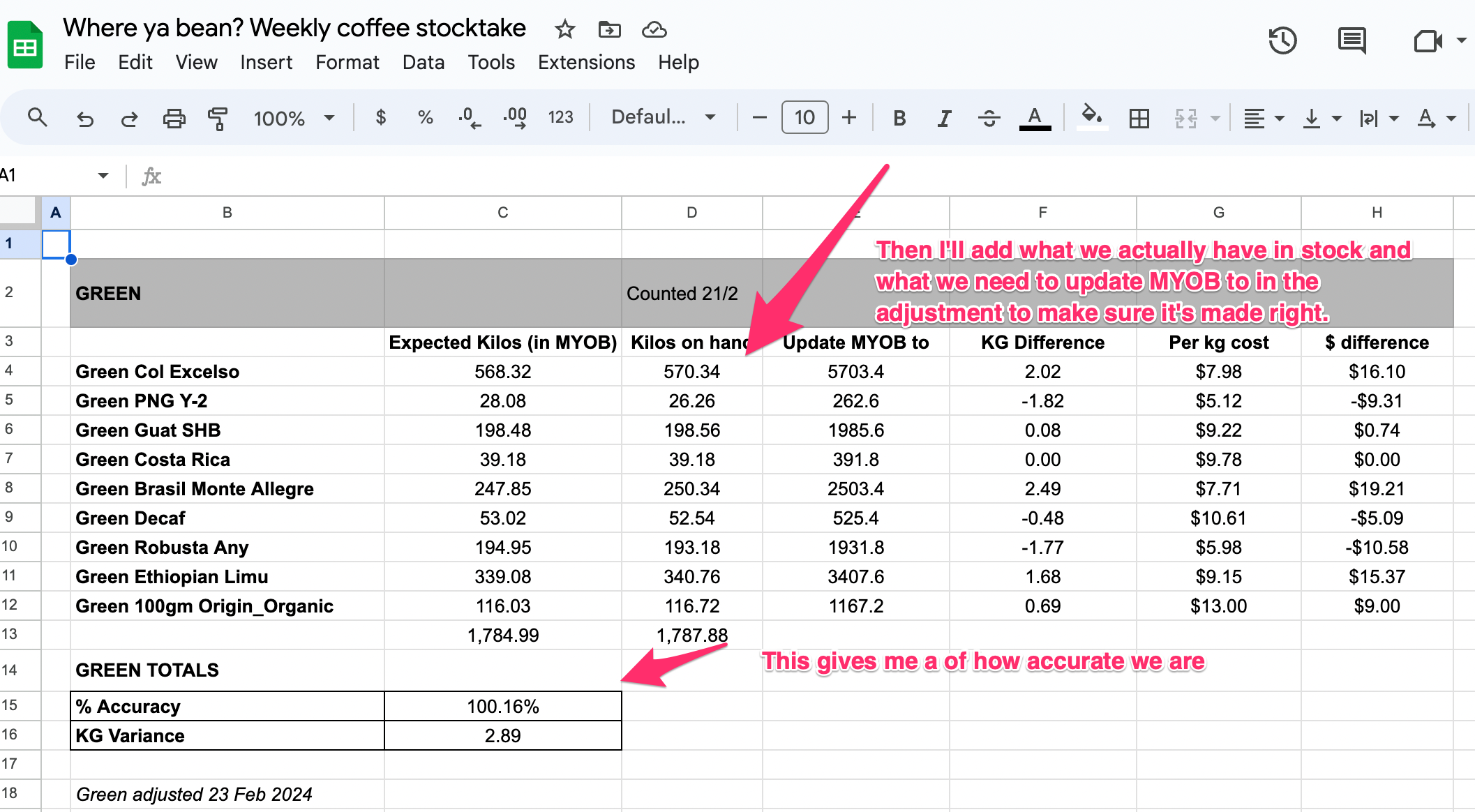

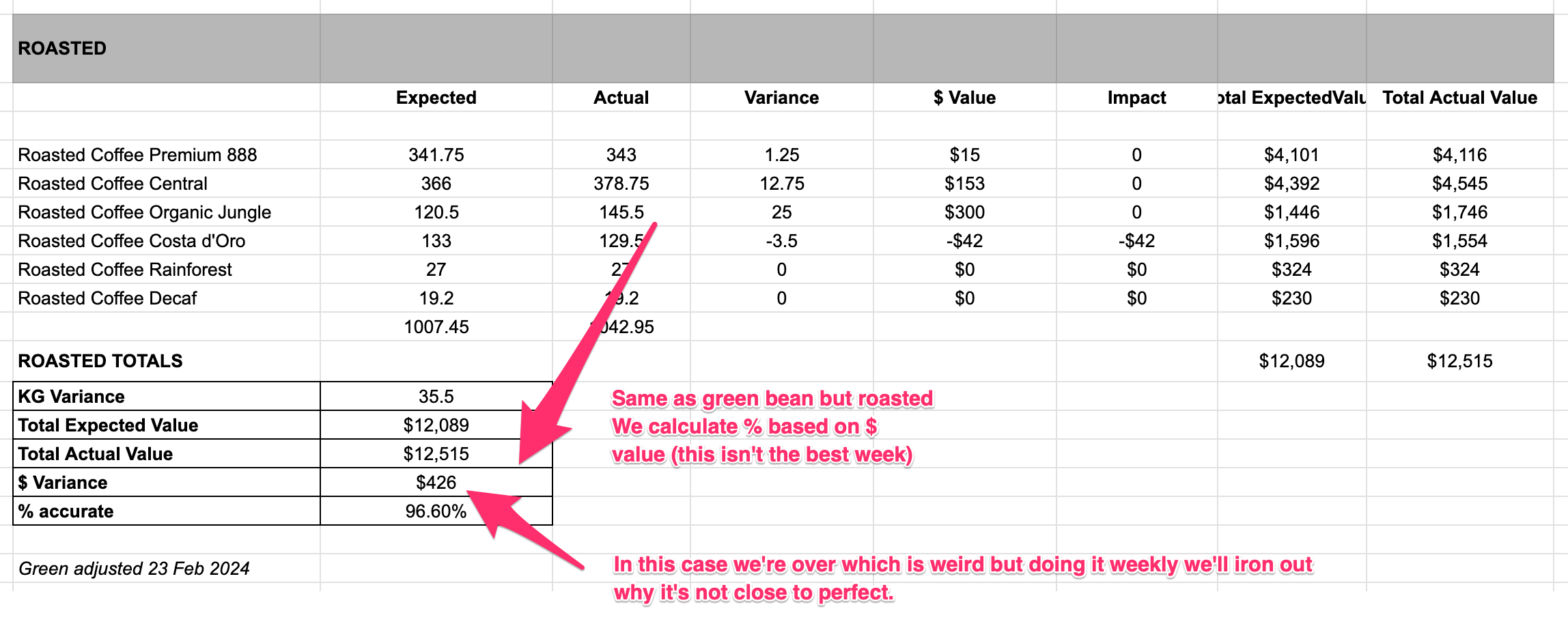

At East Coast Roast I am currently doing this weekly, which is pretty extreme. But I’m doing it weekly because we are still not very accurate (which you’ll see below), and I want to get on top of it. For a physical business, it should be done at least monthly, and once I’m comfortable with how accurate it is, I’ll move to monthly.

Here’s how I do it.

Stock spreadsheet

I have 2 spreadsheets I use for inventory, set up in Google Sheets:

- Non coffee stocktake sheet – this is for everything that the business sells that isn’t coffee.

- Green bean and roasted been sheet – this is for coffee, which is a big chunk of what we do and it’s seperate because it’s very important we get it right.

Inventory adjustments

Once you complete the stocktake, you go into the accounting system and perform an inventory adjustment. This not only sets the stock to the right number, not the expected number, but it importantly marks the difference as a cost on the P&L. That way if you are looking at the P&L each month you are constantly seeing this cost and you’re motivated to do something about it.

What do you think?

I warned, you, possibly the most boring post I’ve written, but I hope it was useful. I’ve re-enabled comments on this blog (try to ignore the cringe ads that Disqus comes with by default). If you have any thoughts on the post above, feel free to add to the comments. Like I mentioned at the top I’m sharing while I’m learning so if you have anything to add I’m all ears.

- RIP Kerwin “Fucking” Rae - October 19, 2024

- Selling my small Aussie hosting / WordPress business - April 22, 2024

- My viral latte art video, and my plan for finally getting on board with video Marketing - April 8, 2024